The One Where Wim Wenders, Yohji Yamamoto, Georgia O'Keeffe and a Naked Emperor Walk into a Bar...

Thoughts on style and imagined identities

The other day I found myself thinking about The Emperor’s New Clothes, the old children’s tale by Hans Christian Andersen. In the story, two swindlers pretending to be dressmakers trick the Emperor and his entourage, convincing them that they are weaving the finest of fabrics for the Emperor to wear. Because they are swindlers, there is no yarn, there is no cloth, but the Emperor, embarrassed as he is unable to see the beauty of the imaginary clothes, pretends to love the garments that are simply not there. The story concludes with the Emperor walking through town, in his make-believe garments, and it takes a child in the crowd to realize that there are no clothes on the Emperor. The Emperor keeps walking, as if not to notice.

I thought of the story after I had spent the best 81 minutes in recent memory watching ‘Notebook on Cities and Clothes’, the fabulous 1989 documentary by Wim Wenders about Yohji Yamamoto. The documentary discusses, among other things, identity, craftsmanship, emotion and the creative process and it starts with Wenders’ experience of having purchased a Yohji shirt and jacket. In a voiceover he says:

“…with this shirt and this jacket it was different. From the beginning they were new and old at the same time. In the mirror I saw me, of course, only better. More "me" than before. And I had the strangest sensation: I was wearing - yes, I had no other words for it - I was wearing the shirt itself and the jacket itself and in them, I was myself. I felt protected like a knight in his armor…”

This early section in the documentary resonated with me strongly. Ever since I was lucky enough to find and purchase a Yohji Yamamoto jacket at the thrift store last summer, I knew there was something different about that particular piece of clothing. When I put it on, it just felt right.

It is a relatively simple black jacket, but was it something about the drape, the fabric or the cut that made it feel so special? I couldn’t quite understand it. When I listened to Wenders recount his first experience with wearing Yohji, I couldn’t believe how accurately he was able to describe the way I had felt last summer, and still feel every time I wear that jacket. I felt, and continue to feel, something significant, something very personal.

Buying the Yohji jacket changed something in me: the jacket has made me reevaluate almost every piece of clothing I own. Very few things in my wardrobe make me feel the same way as that jacket. I’m still trying to figure out what it has that most of my other clothes don’t. What’s obvious to me now though is that the world is full of fashion swindlers that promise you that you will look and feel cool in their clothes… but somehow they leave you either disappointed or wanting to just purchase more stuff.

I’m starting to think that if you want to really feel something in your clothes and have that feeling last, if you want to feel like an improved and protected version of yourself in your clothes, you have to look outside of the usual flashy fashion suspects, and definitely outside of the trend-driven nonsense that most fashion currently is. Clothes are only clothes, but sometimes they are so much more than that. You will feel it when it’s right, but it’s not always easy to differentiate between really good clothes and the swindler kinds. Overthinkers and very visual people like me get so easily distracted.

These thoughts accompanied me when I browsed through pictures of Georgia O’Keeffe’s clothes on The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum’s website some time ago. The museum has archived O’Keeffe’s possessions, including her clothes, of which the oldest date from the 1920s and the newest from the 1980s. O’Keeffe’s digital wardrobe spans decades, and yet she is present in every garment: every white shirt, every wrap dress, every haori, every pair of well cut trousers is so obviously hers. Everything looks thoroughly worn, there are clearly no bad impulse buys there. She bought and wore clothes and accessories that suited her lifestyle, allowed her to paint and do chores in. But the clothes were anything but boring: they had a clear point of view. O’Keeffe owned pieces by Marimekko, Claire McCardell and Balenciaga: all fashion houses, in their own way, revolutionary when it came to form and functionality.

Here was a woman, an artist, with a clear eye for fashion, clothes, and style… and I was wondering where her style came from. What was her process? As I asked myself the question, I immediately realized how ridiculous it was. For the life of me I can’t imagine Georgia O’Keeffe having a style process, asking herself how she wanted to portray herself to others through her clothing choices. O’Keeffe’s style has been called carefully curated, controlled and calculated, but I doubt that she would have spent her free time trying to analyze her own style.

Looking at O’Keeffe’s clothes and how much she wore them, this was clearly a woman who knew who she was and what she wanted. Her style might have been controlled, consistent and intentional, but it was also organic, deep and genuine. She wore what spoke to her, she lived in her clothes. When a person dresses like that, they become the center, not the clothes that they have chosen to wear. And when the person is interesting in their own right, the clothes become interesting, too. Think of Steve Jobs in his black turtleneck and a pair of jeans, or Bill Cunningham, in his blue French worker’s jacket. They wore the simplest things. You and I can buy a black turtleneck and a pair of jeans and get a “Steve Jobs vibe”, but would that be style? No, I don’t think it would be, not on anyone else but Steve Jobs. One person’s style becomes another person’s costume. It’s almost like you can’t separate the clothes from the person. Maybe that’s what style is?

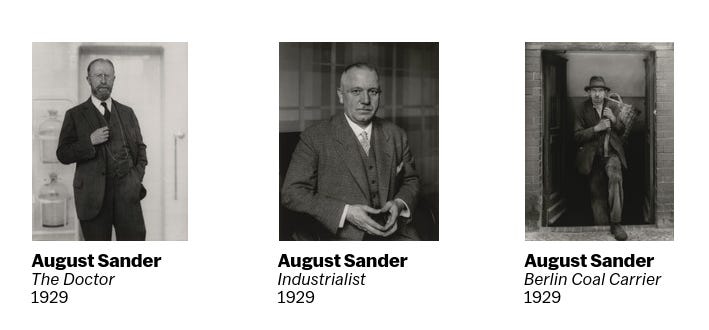

There’s a section in ‘Notebook on Cities and Clothes’ where Wim Wenders discovers that Yohji Yamamoto owns and loves the same photography book by August Sander as he does. The book is called ‘People of the 20th Century’ and it is a book of portraits taken of ordinary and not so ordinary German people, mostly at the beginning of the 20th century.

There’s a famous portrait of a rotund pastry chef in his white uniform, there’s a young poor Roma boy in his worn but somehow beautifully draped clothes. Wenders and Yamamoto discuss how interesting the people are: their faces, what they do for a living, and how that is reflected in their clothing. A lot of the time Yohji doesn’t have to read the description to know who these people are: that’s a banker, that’s a barber, that guy works in a butcher’s shop. It’s obvious who they are, because these people’s identities were intricately linked to their clothing. A lot of that is because it was a different world back then: people were more tied into their social class then than they are now, and people’s paths, be it careers or family, were more often predetermined. I don’t mean to say that things were better then (of course they were not), nor do I intend to turn this into an anti-capitalist rant, but thinking about these old portraits… I was left thinking that there’s something really wrong with the way we buy and wear clothes these days: we buy and wear clothes in order to present an identity that is almost always somehow imagined rather than tied to reality.

As we’ve gained the freedom to wear what we want over the years, our clothes have become very superficial. They no longer represent our place in society the way they used to, and maybe we’re over-compensating because of that. We still recognize clothes as identity markers, but we’ve moved past the time in history when those identities were clearer and tied to our position in society. So now we dress for a “look” that would make us belong: we might try to find ways to feel more like ourselves in our clothes, but we pay increasing attention to how clothes look on us and how others might perceive us, rather than how we really feel in them. It takes a lot of character and a well-developed eye to be able to choose one’s clothes based on instinct, feeling and intellect, like I think Georgia O’Keeffe might have done.

I’m thinking about all of the outfit selfies I’ve taken of myself over the years, and I’m stunned at the realization that what has guided me in my sartorial choices has been the look, and not the feel. It’s not that I’ve sacrificed comfort over a certain visual presentation (the older I get, the more important comfort has become), but what has determined a good outfit has been more often than not based on what the end result looks like on me, rather than a deeper feeling, the kind I get when I wear the Yohji jacket. I’m wondering that maybe, just maybe, if I was a more confident person, if I really knew who I was, maybe the right clothes would almost automatically follow and I could stop buying all this unnecessary stuff that I, on some level, think I need in order to somehow find and then play-act a version of myself.

Here’s my untested hypothesis: if you keep feeling unsatisfied with the clothes that you have and always want more, maybe you’re not dressing for who you are deep inside, but to present an identity to others, to the world. Some people are naturally more character-driven dressers than others (they might actually enjoy the ever-changing identity play), but if you’re not, you might have a desire to belong to a group of people you admire and want to be a part of. That desire, rather than who you really are, is guiding you, and that’s why the clothes just won’t stick, and you keep feeling like something is missing. A part of you thinks that if you just got the clothes right, you’d finally feel like yourself. I don’t think style works like that though. I think style has to come from the person, from who you are.

I’m wondering whether it all comes down to this idea of identity. At the heart of confidence is genuineness. Being true to oneself is all we have: recognizing what speaks to us, feeling our emotions strongly and truly, not accepting false promises, imagined identities, or costumes. Maybe that’s when we really find ourselves, learn who we are, and the right clothes will fit, they will follow our instincts onto our bodies and into our lives. We become one with our clothes. That’s the hope, I guess.

I’m in the process of reaching for the clothes in my closet that I know somehow speak to me and work for my everyday life. I try not to think about what the clothes look like on me so much, I try to focus on the feeling. When I’m in the zone, it’s easy: I grab my warmest cashmere sweater and a comfortable pair of trousers or a skirt, a pair of simple lace up boots, and the same handbag every day. I alternate wearing just a couple of coats even though I have dozens. I’m using A Closet app to track what I wear, and some days when I’m adding images of what I’m wearing on that day to the app I find myself asking “Is this what style is? Could it be this simple?” Most days I feel pretty good in what I’m wearing, other days not so much, but maybe that’s just a part of the process. I’m an over-thinker at heart so I don’t know if I’ll ever get truly settled. We’ll see.

I will conclude with another nugget of wisdom from ‘Notebook on Cities and Clothes’. Here is Wim Wenders again:

One day we spoke of style and how it might present an enormous difficulty. Style could become transformed into a prison, a hall of mirrors in which you can only reflect and imitate yourself. Yohji knew this problem well. Of course he had fallen into that trap. He had escaped from it, he said, the moment he had learned to accept his own style. Suddenly, the prison had opened up to a great freedom, he said. That, for me, is an author, someone who has something to say in the first place, who then knows how to express themselves with his own voice, and who can finally find the strength in himself and the insolence necessary to become the guardian of his prison and not to stay its prisoner.

May we all get out of our hall of mirrors one day.

Further reading and afterthoughts:

This article talks about O’Keeffe being a careful curator of her own image. Side thought: are we interested in O’Keeffe’s clothes and style because she was a woman? I know that Frida Kahlo’s clothing has also been shown in an exhibition. Have there been any exhibits of male artists’ clothes, and if not, why? I haven’t investigated this yet, so I’m just throwing the question out there.

Fun article in The New Yorker about Marimekko’s significance for the modern woman in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Susannah Frankel: Perpetual Revolution: The Paradox of Yohji Yamamoto

If you don’t know much about Yohji Yamamoto, this retrospective in AnOther Magazine is a great crash course.

Imagined identity: my field of study was international politics, and my thoughts regarding the concept of identity being imagined rather than real is based on Benedict Anderson’s classic work (1983) on nationalism and imagined communities. The idea of consumer tribes (Cova, Shankar & Kozinets, 2007) where we associate ourselves with others based on the products and brands we buy is even more interesting in this context. ‘Tibi fans’ is a great example of a consumer tribe!

This was a fabulous piece! I am so excited to read more from you. Thank you for sharing O'Keeffe's wardrobe. Was a treasure to look through. The color palette was almost predictable...as I clicked through looking for the lone red pieces. Much of it reflects the color palette of her paintings, those colors being the ones that resonated deeply with her. Within my own wardrobe, I find myself drawn to the colors I connect most deeply with, red, blues, chartreuse, deeper yellows, and whites. My closet consists of mostly vintage(probably over 90%), and many of the pieces have been gifts from an older friend who used to have her clothing made by a seamstress in 1950s Israel. The pieces with these older kinds of stories are the ones I feel most comforted in. I often look in my closet and ask what could be parted with(mind you I don't have a massive wardrobe), and it is the modern clothing with poor construction and fabrics that always make the cut. I've since stopped buying pieces made of poor fabric, and it has helped how I feel day to day. One last note, I believe our true personal style very much connects with our childhood. What was it as a child that you wore that didn't make you think much about your body and could just be? Mine was this 90s gauzy sundress with a mauve and purple and black print that felt like nothing. It had buttons, and eventually tore because it was gentle fabric, but that was the one. Understanding what I wore back then, I can connect why certain pieces I have in my closet today resonate with me. I am ever collecting vibrant, patterned, and outrageous pieces as a way to connect with my inner child. My wardrobe will never look like the minimalist and calm pattern of Georgia's, but that is ok. I hope that someone might find as much joy looking through the contents of my wardrobe when I am passed.

You might find the book 'What Artists Wear' by Charlie Porter interesting; I saw it in a bookstore recently and very much enjoyed leafing through it (it features both male and female artists). I also recently unpacked my books and I found my old copy of 'The Fashionable Selby', and it was actually inspiring, to see personal style documented before the current era of the digital influencer. It feels much less perfect, much more personal, more a feeling, less a "look".

So much of what you write here resonates with me...perhaps we are so interested in personal style because modern life is so concerned with image and we are bombarded by imagery at a pace that leaves little time for reflection.

I reckon Georgia O Keeffe had her "off" moments when it came to dressing herself, I only wish I knew what she thought of them!

Looking forward to more of your style thoughts, and thank you for launching this newsletter!