Die, Sportswear!

Investigating ‘friction’, womenswear discourse, and why athleisure is never going to work for me

It occurred to me on Thursday, as I looked at myself in the mirror, my clothes resembling those of a linen-clad rice farmer from an alternate dimension, that I really, really, actively dislike sportswear. My clothes that day felt very much like me: there was romantic drape, subversive volume, and comfort to boot – simplicity and complexity all in one. I sometimes feel a little bit out of place in Helsinki where half the female population seems to be wearing leggings, bike shorts or running pants. Not a single element in my outfit that day felt sporty, and I felt great. My thoughts about athleisure have been slowly percolating around athletic shoes in general and my distaste for dad sneakers in particular, but they came full circle during chaotic culling, where I instinctively purged my closet of things I didn’t care for. The pile of clothes that didn’t make the cut included hoodies, a baseball cap and a pair of god-awful white high-top sneakers. The common denominator of these clothes is athleisure.

I have never cared for sports. My least favorite experiences at school have to do with track and field and PE in general. I was typically the last to be picked for a team sport and one of the last to reach the finish line when running was involved. The only sports I even remotely liked at school were ice-skating and Finnish baseball, but only after my best friend at the time took painstaking time and effort to teach me to perform crossovers and to bat, respectively. The emotions that I associate with PE at school in the 1980s and early 1990s include humiliation, embarrassment and fear.

Because of my aversion to sports, it follows that I have no positive memories of sportswear. I have a particular animosity toward clothes made of technical textiles, like windbreakers, football/soccer jerseys or track pants. The Adidas three-stripe track pants are my own personal version of hell – the kids who bullied me at school wore them with their hoodies, bomber jackets and cool-kids-sneakers.

Earlier this week I found an archived IG outfit post from November 2020, where I wrote in the caption: “here’s a shocker: sometimes I wear sneakers when I go out for walks. I’m more of a lace-up walking shoe person, and I’m very much against the ‘dad sneaker trend’ and I loathe sneakers worn with dressy clothes. I say ‘loathe’ but really they do look very cool on some other people.” I wondered in the post whether I’d soon find myself wearing dad sneakers the way trendy people did then. That never happened, but a few months later, in early 2021, I shared outfit images of myself wearing hoodies under my coats. I had bought two new pairs of sneakers – the plain black pair that I still sometimes wear if I need to walk a lot and my feet hurt, and those aforementioned terrible white high-tops. From the way I tucked in my sweaters in the pictures I could tell that my experiments with hoodies and sneakers coincided with my discovery of Tibi Style Class. Ah, the irony of being influenced against one’s own better judgment!

Amy Smilovic, the creative director of Tibi, always talks about the importance and the necessity of knowing oneself and of reflecting one’s inner self in one’s clothing choices. She’s great at verbalizing why some style aspects work and why others might not. Amy promotes her own brand and the aesthetic that is known in the Tibi-verse as “chill, modern and classic”, so Style Class revolves around Tibi products and their styling in a way that doesn’t take into consideration other aesthetics or approaches to personal style. Amy is very open about it and she will often say things like: “and if this isn’t for you, that’s fine”. That didn’t stop me from immersing myself in the world of Tibi in 2020 and 2021, even though I should have known that the aesthetic it promotes does not align with my own and there was a chance that I might get caught up in it.

I lost my style compass for a while after going down the Tibi Style Class rabbit hole. I am certain that my dabbling with sportswear in 2021 and onwards came from Tibi, because the Tibi style lexicon is packed with sportswear influence and up until quite recently I had trouble making sense of a lot of things, stylewise. Amy is very direct and often persuasive with her opinions. In a recent Substack newsletter she writes about severely tailored, nipped in blazers: “MqQueen’s [sic] are beautiful, undeniably. But it can hardly be described as effortless. In fact, it reeks of effort.” She doesn’t follow this statement with “but if you want to reek of effort, that’s fine”, but the message is pretty clear. Obviously no one wants to reek of anything, and if you’re uncertain about your style, about who you are, or if you’re in the midst of personal turmoil, it’s pretty easy to get sucked into taking these types of statements at face value, without investigating what you actually like and what you don’t like. (It’s worth noting that it’s actually fairly difficult to talk or write about very specific style questions without accidentally shitting on something that someone else might love.) Like Amy says, you have to really know yourself, because otherwise you’re free game for all sorts of style influence and you’ll end up wearing other people’s ideas and opinions rather than sticking up to what you feel is right for you.

It still seems almost impossible to me that I ever bought those white high-tops. How did I manage to talk myself into it, when sportswear has always left an unpleasant taste in my mouth? Why did I feel compelled to wear a neon yellow hoodie with a tailored coat, or sneakers with my tuxedo trousers?

I believe it comes down to the notion of ‘friction’; the idea that in order for style to be ‘good’, it is necessary to pair contrasting elements and to mix aesthetics in one’s style. The goal is to not look ‘too obvious’ or ‘boring’, so we are encouraged to wear track pants with a blazer, sequins with army fatigues, and everything with ‘the wrong shoe’, to ‘create friction’. The friction advice has been floating in women’s style discourse for some time now, and I see it successfully in action on other people quite often. People like Jenna Lyons, Kate Moss and many others who cultivate the friction approach always look great in their highly friction-y clothes.

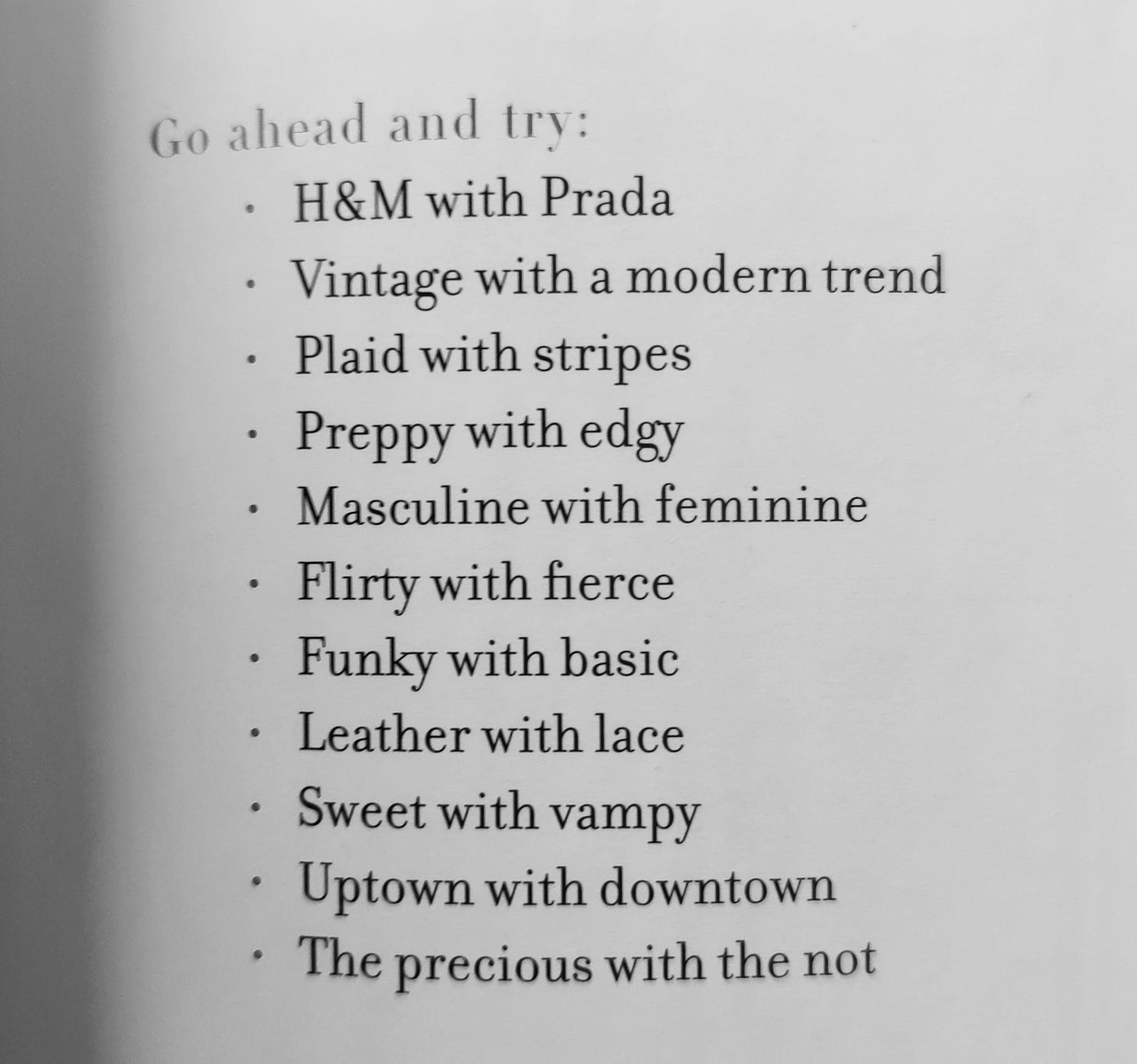

Nina Garcia made the case for mixing up different aesthetics in her 2007 book, The Little Black Book of Style:

“Anything that sounds like it won’t make sense usually looks amazing. The uptown with the downtown. The soft with the hard. The casual with the elegant. Trust me, it works. Unpredictable is far more interesting than predictable. It is what is going to make you look different and interesting, which is the hallmark of a stylish woman. Mixing it up is not about looking staged. It is supposed to be personal. [...] Style is about these imperfect mixes and these unusual juxtapositions, it takes time and trial to perfect the mix. It can’t look staged, it has to look effortless.”

When I dabbled in sportswear I obviously went looking for friction for the sake of friction, and what would be more contrasting to my being a giant nerd than trying to insert chill, cool and sporty vibes into my personal style? When I wore a pair of sharp trousers, I swapped my gentlemanly walking shoes for sneakers. While wearing a more feminine skirt, instead of covering my head with an elegant silk turban like I used to, I opted to wear a sportier beanie or a baseball cap. I teamed my merino wool knit skirt with a padded bomber jacket instead of a tailored wool coat. I probably looked fine to an outsider and maybe even more current than my usual outfits would have, but I felt like a total jackass.

The hunt for friction led me to buy and wear things that I don’t think looked (or felt) nice, like flat pointy-toed mules that so many people on IG complimented, and for the purpose of this particular newsletter, things I actually hate to wear, like a baseball cap and those hoodies and sneakers. The imposed notion of friction encouraged me to travel beyond my aesthetic, which was probably supposed to feel like a world of fun, but it didn’t materialize into anything other than unfortunate outfits and alienation from my sense of self. Looking back, the outfits remind me of my worst times as a shopaholic when I ran after seasonal trends and had a wardrobe full of a little bit of everything, and how unmanageable my wardrobe was back then, with various aesthetics engaging in a perpetual tug-of-war. When almost anything could be the friction that one’s outfit might need, it becomes awfully difficult to rule things out when you’re trying to figure out what to wear or what to buy. Everything becomes an option, too many options leads to uncertainty, and uncertainty, for me, is the death of personal style.

I believe that the idea of friction can be fruitful, but I’m reminded of the fact that menswear style advice never encourages the reader to dabble in friction from the get-go. Friction in menswear is only for the highly advanced, and the reader is advised to stay carefully within the bounds of their own sense of self and play only after they know what they are doing. Whereas women’s style advice tends to focus on frivolity, fun, quick cheap thrills or irony when it comes to friction, menswear style advice leans on depth and a deep sense of understanding oneself. No self-respecting menswear style guru would suggest wearing a cheap souvenir t-shirt with a tailored suit to create friction in your wardrobe.

I align with Derek Guy, who has talked about leading with aesthetics and coherence when you are developing your personal taste and style. There’s great comfort and freedom in knowing what you are instinctively drawn to. You can take a deep dive into that world, learn more, and master its details. It then becomes evident, like Guy writes, that “rules about colors, silhouettes, proportions, and other such ideas are contextual to the aesthetic you’re trying to create” (my emphasis). You can bend the rules only after you know them by heart. He argues that personal style is like a language, and the wider your vocabulary and the more nuanced your knowledge of the grammar, the more accurately you will be able to express yourself, and to also play with it. It follows that athleisure and sportswear were always going to fail me, because a) they are deeply inauthentic to my sense of self, b) they don’t exist within my preferred and chosen aesthetic, and c) they speak another language entirely. It’s like Guy says, “like trying to apply English grammar rules to Chinese”. It’s obvious to me now that I was trying to learn my own language by using someone else’s grammar and dictionary. No wonder it didn’t make any sense.

I often wonder why women’s style discourse lacks the type of focus that the menswear discourse enjoys, and why it’s almost always the latter where I get my personal style a-ha -moments from. Women’s style discourse seems to be awfully wrapped up in products and shopping, and there’s always that strange, snarky underlying sense of “if you want to look cool and be accepted, this is what you should be wearing”. There’s a lot of well-intended talk about the importance of being who you are and expressing your true self with your clothes, but somehow we can’t seem to shake a certain preying, consumerist undertone or the feeling that maybe we should still try to be someone else entirely. The sustainable style discourse can be helpful, but its tone can feel preachy and a little tired sometimes, like Jess Graves recently wrote in Substack Notes. (Yes, I felt triggered.) Tibi Style Class is a rare bird because it makes a serious attempt to build a theoretical framework for getting dressed, which is extremely valuable in itself. The trouble is that the theory is for the most part specific to the Tibi brand and its aesthetic, and I get that. It’s a business, after all.

Menswear style discourse is a different creature altogether. I’ll take an example. The legendary menswear style expert G. Bruce Boyer writes about selecting a shirt collar style in his book ’Elegance’ (1985) as follows:

“Different collar styles and shapes, like clothing generally, tend to convey or suggest different moods (from the breezy to the very proper). In selecting a collar style, the question should be, Will the moods that its design suggests accord with the personality of the man who wears it? The idea that some men shouldn’t wear a certain style because of their physical appearance – apart from the proportionate concerns – is rather nonsensical. Clothing changes one’s appearance – that is its function – and the question is whether or not a man’s personality fits the appearance his clothes create for him.”

In a different essay in the same book, Boyer writes several paragraphs on how to choose a shirt, and how to navigate the ready-to-wear shirt jungle as well as the custom-made one. Alongside collar style, he discusses cuffs, chest pockets, monograms, placket buttons, squared tails, French seamed front, and other details. I don’t know of any womenswear writer, past or present, capable of this type of exhaustive analysis of a single garment. Nina Garcia’s two paragraphs on the topic of a white man's shirt as an iconic piece of clothing in a woman’s wardrobe simply state that the classic white shirt is “chic and simple. Practical and unpretentious”. She then lists various famous women who have successfully worn white shirts, concluding: “Any time a cool girl or a designer throws a man’s shirt into the mix, we are reminded of the power that comes with that crisp simplicity. And is there anything quite so sensual as seeing a woman in a man’s white shirt?”

This rather shocking difference in treating a topic such as a simple shirt shows that what is missing from the womenswear style discourse is eloquent, knowledgeable, detailed and honest writing about women and their clothes, where the goal is to not sell anything other than expertise. Whereas (predominantly white) men’s style discourse has a deeper tradition that aligns with men having enjoyed relative ‘freedom of self’ for longer than women, historically women’s style discourse has been aimed at keeping women in their place and/or selling them the latest fad. I believe it was only in the 1980s when mainstream style advice aimed at women began to slowly loosen up from its bounds of domestic life, and women were finally seen as subjects rather than objects. We’re better off now than we were before, when most womenswear guides told us to more or less just look as pretty as possible in order to please our husbands, but we still have ways to go to reach anything that resembles a coherent discourse that doesn’t dumb down the conversation and dismiss the complexity of our clothing choices.

Style advice that focuses on a woman’s body shape is still frighteningly common, and it typically fails to be empowering. Women are still told to choose from existing style stereotypes (“are you a romantic or a rebel?”) and to buy “20 pieces of clothing every woman should own”. It is only very recently that the notion of dressing for who we are as people has begun to surface, but that, too, is often buried underneath sponsored content or affiliate links. It’s not exactly helpful that in the social media era almost anyone and everyone can pose as a style expert. I recently came across a personal stylist and thrift bundle seller on IG with more than a 100,000 followers, and the stylist in question called a wool overcoat “a fur trench” and mistook a 1990s Hennes & Mauritz (aka H&M) blazer for an imaginary Hermès collaboration piece with the fast fashion brand. I know that nobody is born an expert and beginners will make mistakes, but it scares me a little that these days clicks seem to equal expertise.

Menswear style advice consistently stresses quality, whereas the womenswear discourse tends to focus on brands and their social caché. Menswear writing discusses fabrics and workmanship in the minutest detail, whereas womenswear discourse misses the complexity of these topics and says things like “here’s a linen shirt for every budget”. It seems that at every turn, womenswear advice cuts a corner for a quick return, whereas menswear advice patiently builds a case that will stand, no matter what your personal style or preferred aesthetic might be.

I feel that I’m knowledgeable enough to be able to read the great menswear writing that’s out there and to apply it to better understand and solve my own personal style battles, but that approach might not suit everyone. I am not sure where that leaves most women. I am of two minds. On the one hand, I try to have faith that platforms like Substack can cultivate talented womenswear writers and perhaps encourage them to create something truly valuable to develop the womenswear style discourse. I believe that the best womenswear content currently comes from Subrina Heyink, who will discuss in detail things like Nicholas Cage’s personal style, whether Zendaya actually has any real style to speak of, and the perils of trying to find your personal style. Her most recent piece on what to wear to a wedding is fabulous, too. On the other hand, I crave a deeper change, where we could go back to a time where fabrics were made to last, where trends didn’t come and go this fast, where brands, shop assistants and consumers wanted to really get down to the nitty-gritty about the clothes they were manufacturing, selling and buying, and where there was more room to breathe. It’s pretty obvious that the latter will not happen, so I will optimistically put my eggs in the first basket.

In the meantime, I’m coming to terms with the fact that I am still that nerdy girl who hates track and field and loves history, and that is reflected in what types of clothes and accessories I like and want to wear today. Friction, be damned, and sportswear with it!

Your post makes me think of this notion (highly enabled by the industry) that "men have (style) uniforms, while women have Fashion." The rate of change in men's fashion happens at a glacial pace (if at all, for some pieces) compared to the frenetic pace of women's RTW in the modern fashion age. So it's not surprising that many women who care to build a wardrobe of more enduring pieces end up leaning on many menswear-inflected, tailored pieces to anchor their style.

Personally, I love working in athleisure/sporty elements in my wardrobe but that's because it's a way to incorporate certain other aspects of my life I love (ie: I enjoy fitness, and some sports) into my style. Choosing elements that add 'friction' is a fine personal style strategy, but those elements, as you say, need to actually meaningfully resonate for you on a personal level. Otherwise it just becomes a chaotic grab-bag of dissociative elements instead of a cohesive personal style.

I've been thinking about this topic a lot, meaning: style that exists within a logical and consistent framework specific to -a person-, not a framework dictated by a designer or anyone else.

My style is absolutely consistent, and has been since the late 80s. I rotate different silhouettes in and out, and pay attention to trends (I sample the things that work, only), but I'm not ruled by them.

I also followed Amy Smilovic for a bit, during the pandemic. I like that she's figured out her own framework, and has exposed it as the logic that drives her work for Tibi. Like you, I didn't find that her framework was my framework. The "three words" thing doesn't work for me at all, and "chill" means something quite different to me than it does to her (and forget "friction," I prefer "harmony"). And that's fine.