In 1965 Alfred L. Yarbus, a Soviet psychologist, published his seminal study, ‘Eye Movement and Vision’. With his pioneering work on saccadic exploration, Yarbus was able to track and record the way we look at complex pictures. Our eyes move back and forth between certain areas of the face, for example, as we try to make sense of what we are seeing.

Yarbus’ eye movement study had the test subjects looking at ‘They Did Not Expect Him’ (1884-1888), a famous painting by Ilya Repin. First the subjects looked at the painting without any particular prompts. Their eyes wandered naturally to the faces of the people in the painting. A later prompt asked the subjects to observe clues about the social class of the people in the painting. The eyes wandered to the clothes.

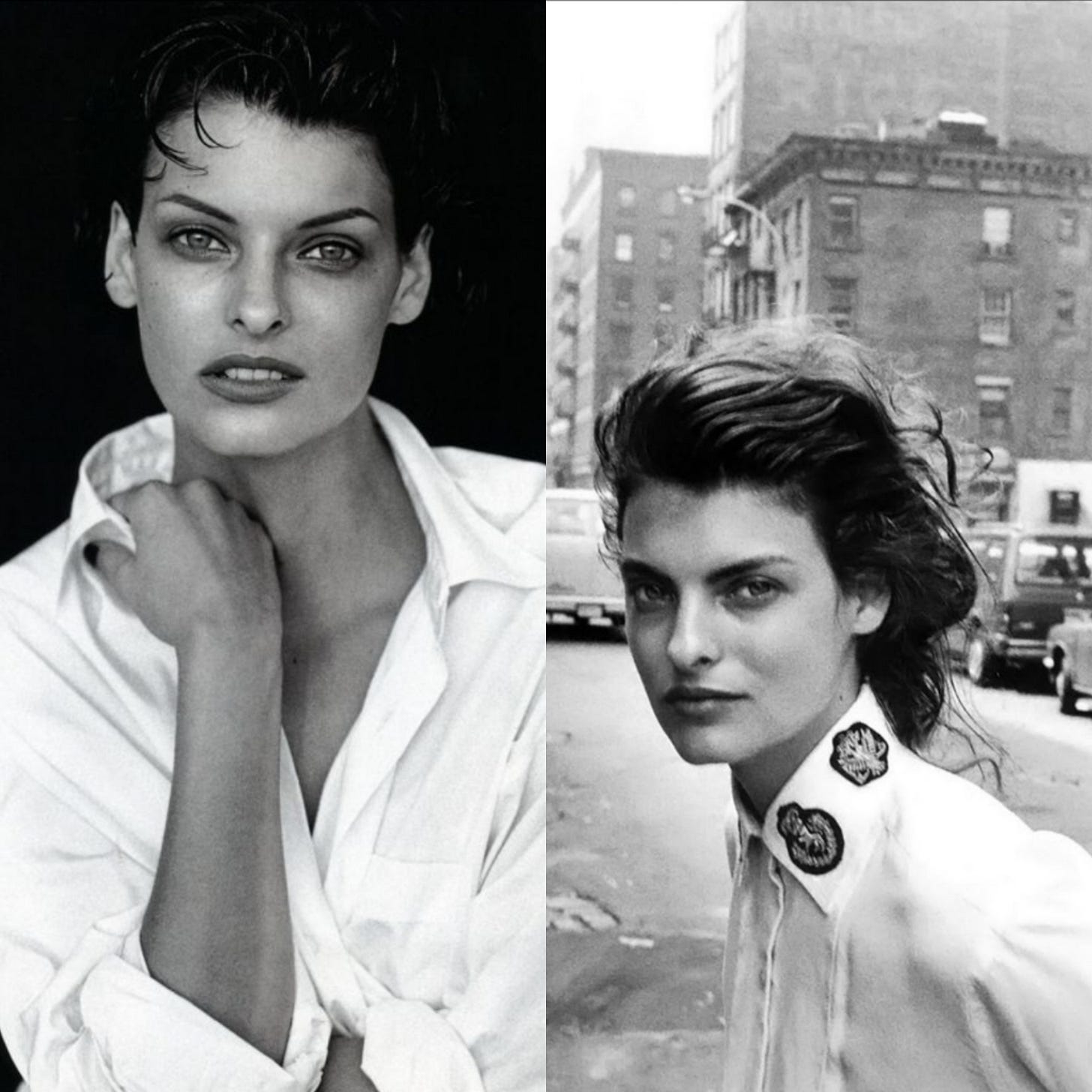

I found myself thinking about Yarbus when Pinterest suggested a series of black and white fashion photographs of Linda Evangelista for me to look at and save. I always stop in my tracks when I see Linda. Many of my all time favorite fashion photographs are of her. It’s never the clothes that she wears in the photos that catch my attention, but her face. The late photographer Peter Lindbergh, who was responsible for capturing many of those amazing portraits of Linda, once said: "A fashion photographer should contribute to defining the image of the contemporary woman or man in their time, to reflect a certain social or human reality.”

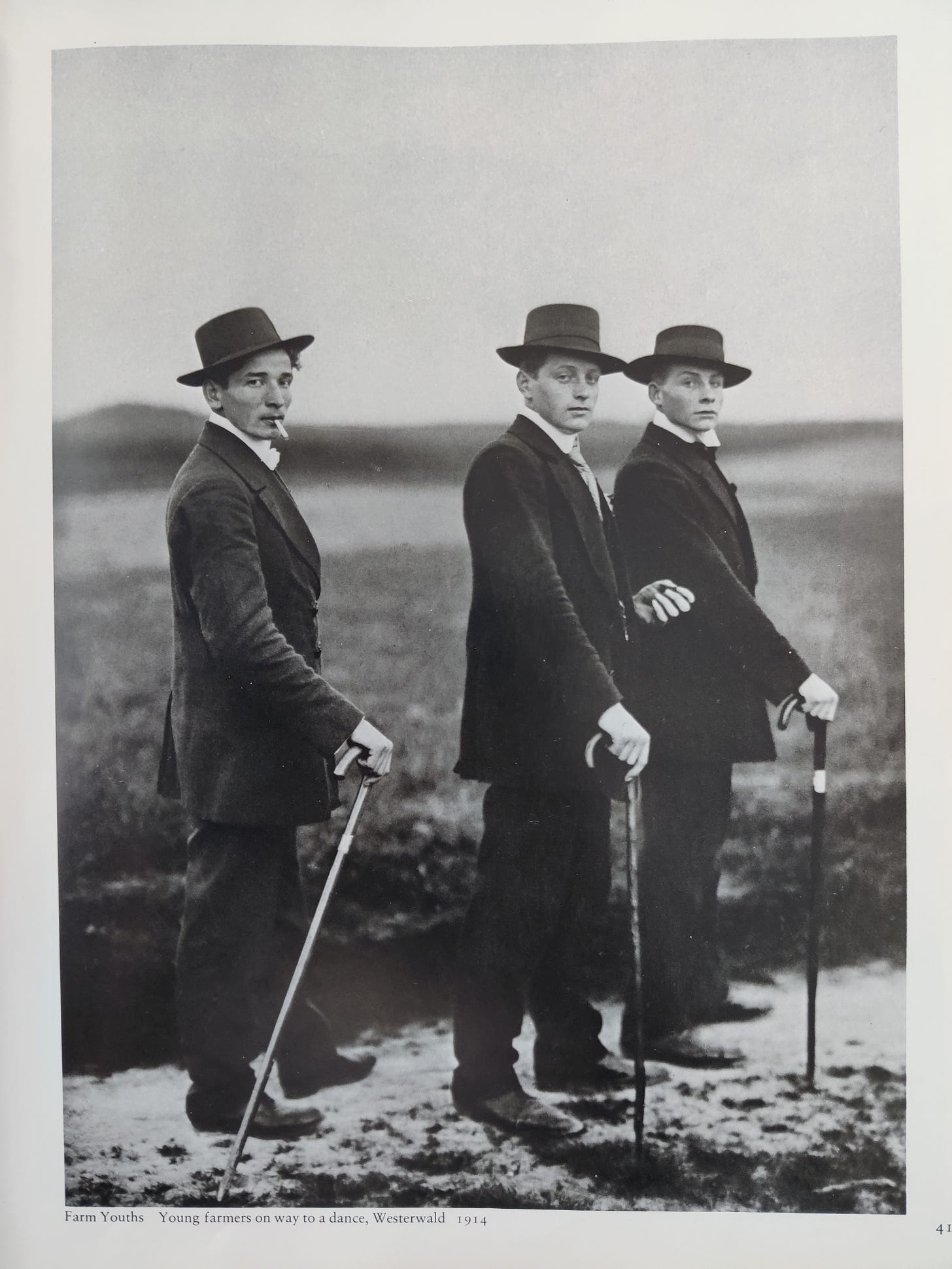

The idea that photographs of people should reflect social and human reality reminded me of the philosophy of August Sander (1876 - 1964), the German portrait photographer, whom I have written about in this newsletter previously. Sander’s approach to photographing people was based on his version of the concept of physiognomy: that a person’s face portrayed that person’s social position. Sander was interested in cataloging humanity and its class system, and his seminal work, ‘People of the Twentieth Century’, attempts to show a cross-section of society under the Weimar Republic.

There’s a scene in ‘Notebook on Cities and Clothes’, the 1989 Wim Wenders documentary on Yohji Yamamoto, where we see Yohji flip through ‘People of the Twentieth Century’. When Wenders asks Yohji why he’s fascinated by Sander’s stern, realistic portraits of people – peasants, workers, industrialists, politicians, academics, circus performers – Yohji responds that in the photographs, people are “wearing not clothing, but wearing reality. People don’t consume the clothing. People can live life with this clothing. I want to make something like that.” The idea that people don’t wear clothing but reality is a thought-provoking one, especially in current times when we seem to be consumers first and people second, and what counts as ‘reality’ is in flux.

Lin of Out of the Bag recently wrote about ‘Irving Penn: Small Trades’, another formative series of black-and-white portraits where the borders between people and the clothes they wear blur into nothingness. The clothes that the electricians, lorry washers, charwomen and butchers wear in Penn’s photographs are often dirty or torn. In stark contrast the bell boys, the waiters and the policemen wear crisp and clean clothes, a presentable uniform to be inspected by other people. The people in the photographs are, indeed, wearing reality, and while their clothes are certainly interesting, my eyes always travel to the people’s faces, just like Yarbus’ test subjects’ eyes did. The people’s faces make the photographs real and meaningful. Without the people who wear the clothes, what’s there to look at?

There’s power in a face. Newborns are drawn to faces at three months of age, and at seven months they can already recognize emotions on a person’s face. Faces contain vital information that’s necessary for various forms of social interaction: we can look at a face and find evidence of a person’s identity, age, sex, health, mood, and what they are thinking or feeling. Through face perception we become social beings.

After recently seeing ‘Memoria’, a fascinating 2021 film directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul and starring Tilda Swinton, I found myself asking if I actually care what people wear if they have an interesting or intriguing face. Tilda Swinton wears unremarkable, even ill-fitting clothes throughout ‘Memoria’, but I was still mesmerized by her. I’ve thought about other people whose style I think I’m drawn to, like David Bowie, Neil Tennant, Georgia O’Keeffe, Charlotte Rampling or David Byrne. They, too, have slightly unconventional, intriguing, quiet, but expressive faces, alongside their amazing talent and serious brains. They are interesting people with interesting faces. At the end of the day I don’t really even care what they wear. What I perceive as their ‘style’ is the person underneath the clothes, not the clothes themselves.

In current style talk we keep hearing that we can and should use our clothing to reflect who we are on the inside. It’s tempting to believe that if we buy the right clothes and style them the right way, then others will somehow witness who we are. We embark on complicated journeys to analyze and define ourselves, and then jump through hoops to find the clothes that would match our sense of self. It’s a peculiar exercise, because who we are and how people see us and interpret us is right there, staring at us in the mirror. That doesn’t mean that our clothes have no significance, but we may be giving our clothing a lot more emphasis than we ought to. Clothes can communicate status, convention and group identity among other things, but without the person inside the clothes, they’re just pieces of fabric.

The Peter Lindbergh quote above, about how photographs of people should reflect social and human reality, continues: “How surrealistic is today's commercial agenda to retouch all signs of life and of experience, to retouch the very personal truth of the face itself?” When we choose to turn away from the power and the significance of our own face, not to mention the faces of others, we are seeking to alter social and human reality. We are missing out on what makes us connect to one another in the first place.

I resonate with your sentiments in this great piece, Tiia. Especially this: "What I perceive as their ‘style’ is the person underneath the clothes, not the clothes themselves." I am also drawn to Tilda, Georgia, and to similar kinds of interesting (but not necessarily conventionally "attractive") people like Susan Sontag and Joan Didion, for example. This quote makes sense to me when I think of all of them. I'm drawn to qualities about the person and their personality and their clothes are somewhat of an afterthought, just a logical extension of the person, but they are not the main event, they just play a supporting role. Your post makes me realize that I may in fact be more interested in just expressing myself/being myself than I am in fashion per se. This also means that my emphasis would be more on becoming/unfolding into myself first with clothing/style choices second, as opposed to the other way around. Having taken a 2-week break from IG (which will go longer now), I've already noticed that my creative expression and my imagination re: style feels freer to explore clothes from a more whimsical place rather than from a consumer mindset of thinking I need to have the latest pieces or to fill in gaps or to look good for FOMO's sake. It resulted in me purchasing a vintage shirt and sweater on Etsy (I personally almost never buy vintage) and neither of these pieces do I "need" or will fill holes in my closet or anything rational at all, but rather my creative self just dreaming of wearing them. I hope this distinction makes sense. It's a welcome psychic shift for me.

I feel this way when I see the clothes at the Costume Institute at the Met. Without the human they fall flat. I wonder why this is why I am bored watching runway show videos, all those generic models uniformly and glumly projecting the brand’s aesthetic. Rather see the clothes IRL, or at least editorial.