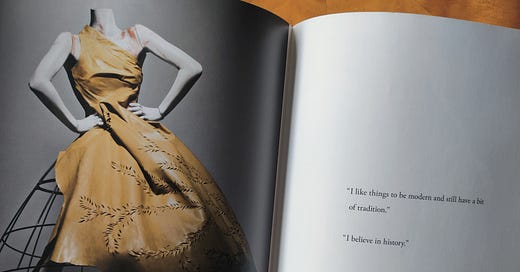

I had planned to write a spontaneous newsletter last Sunday, but I made the mistake of watching Seán McGirr’s confusing collection for Alexander McQueen the night before. After what felt like a restless, anxious sleep, I woke up to Enya’s ‘Orinoco Flow’ looping through my brain. I was done for. I spent the day flipping through Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (2011) and watching old McQueen runway shows. There would be no writing, only contemplating.

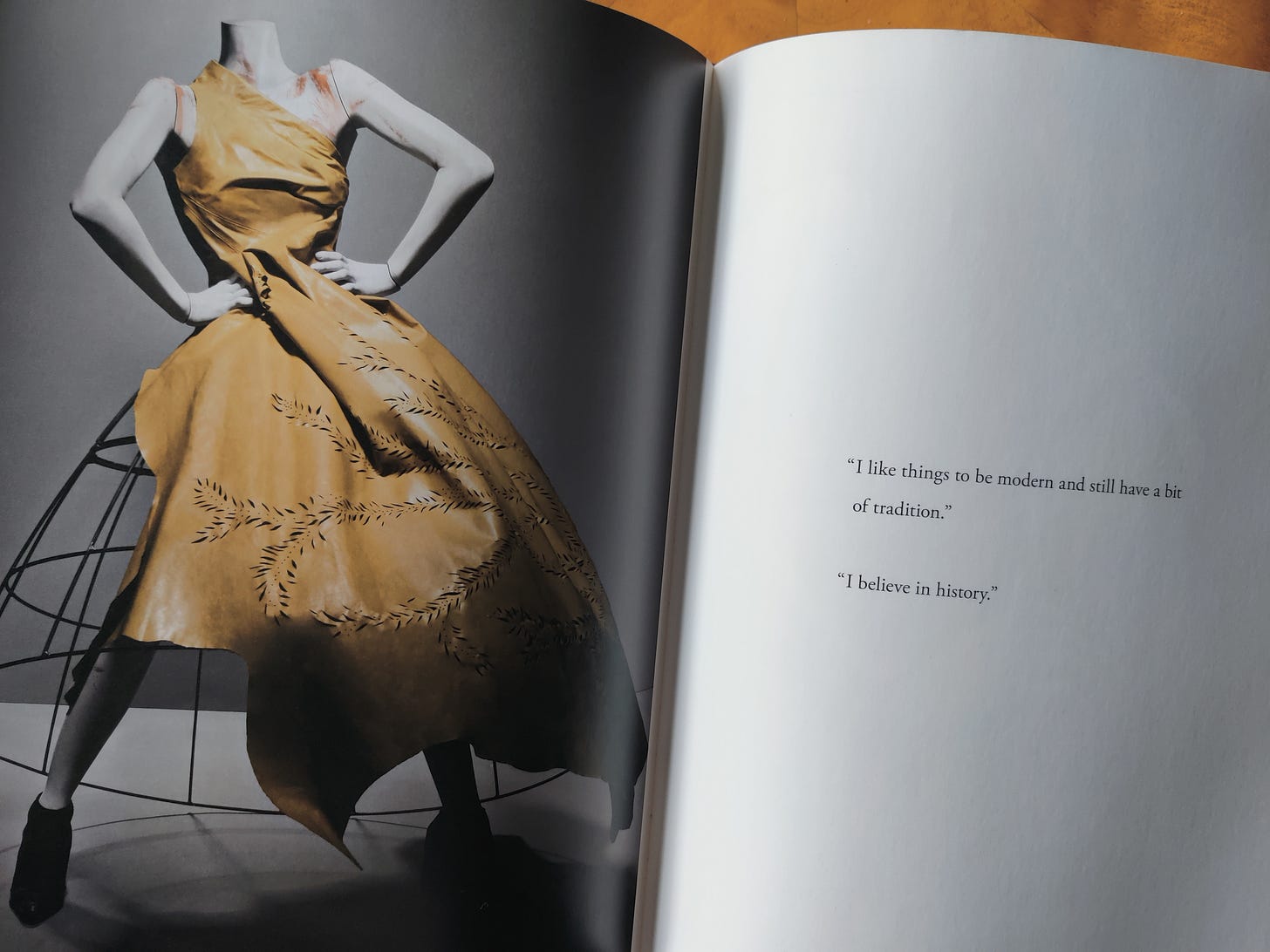

In the days that followed I came to find a deeper understanding and admiration of Lee McQueen’s work, especially in the way it relates to history, sentimentality, and craftsmanship. Lee McQueen was a romantic and a romanticist, and his interest in history ran continuously through his body of work. It was not history for the sake of times past, but because what we consider modern has to have history to fall back on. Otherwise history is meaningless, as is today. History gives us context.

For some time now I have been captivated by historical clothing on the one hand, and our emotional connection to clothes on the other. I’m intrigued by what people used to wear and for what purpose, and why it seems to be so hard for us to find meaning in our clothing now. I keep going further and further back in time in my research, and sometimes it’s difficult to pin down whether I’m looking at costumes or clothes, and how to tell the two apart. The more I investigate, the more peculiar it feels to consider my personal relationship to my own clothes, or to observe other people wearing their clothing. Style and fashion is a complicated web of meanings, symbols, communication, social structure and control, and the deeper into this web I dive, the more challenging it is to feel like the individual has any agency in the process of getting dressed. The disposable nature of current fashion, trends and style-related rhetoric makes it even more difficult. We’re so busy moving forward that there’s very little time to look back and to connect the dots, to see where we were and to recognize how we got here.

Lee McQueen once said: “I want to create pieces that can be handed down, like an heirloom.” He disliked mass production, and he was interested in manufacturing clothes by hand instead, leaving behind a certain silhouette, like a signature. This line of thinking seems almost absurd in today’s fashion, where most creative directors (we don’t even call them designers anymore) are considered universe builders, commercial forecasters or agitators rather than garment makers. For many consumers clothes are mere pictures or raw material to use as we navigate for our place on the identity map. We buy more clothes than ever, and we wear them for a very short time before discarding them. (Sustainable fashion website Project Cece gathered some pretty awful data about the way we buy and wear our clothes back in 2022, and things most definitely haven’t improved since.)

I feel like a bit of a dinosaur, always harping on about this. Yes, we know that perpetual buying is bad. Yes, we know that we’re supposed to appreciate and wear the clothes we already have. It’s just that the system is not geared for us to make a change. The system is interested in producing clothes that we can’t really feel an affinity toward, even if we tried. The vast majority of current clothes are silent. They have no stories to tell, and even if they did, we’re not attuned or around them long enough to hear them. (I’ve previously written about the soul of clothes here.)

The craft of making clothes and the way we buy and wear them has changed dramatically in the last, say, forty to fifty years. At work in my vintage shop I often come across the types of old fabrics that you can’t buy anywhere anymore. The cottons that withstand boiling are crisp and delicious. Old 1940s viscose crepe drapes like a waterfall; heavy, heaving, alive. What is visible in the fabrics and the clothes that they have become is the human hand and craft. In these clothes the stitches are short and tight, buttonholes are made by hand, and the lining is just as important as the top material. The older the clothes, the louder they seem to be whispering and communicating. What scares me is that we’re losing our ability to listen to even the oldest of our surviving storytellers. A lot of people don’t seem to understand what’s so special about clothes that date from the 1920s or the 1930s. They’re too busy thinking about things like practicality, cost-per-wear or their personal brand to recognize truly old clothes as anything else than a pile of fabric that they could use to ‘pull a look’. Finding affinity with clothes requires knowledge, but above all sensitivity and stepping out of one’s role as a consumer.

I celebrated my 46th birthday in February and bought myself a present: a long, black, Dutch skirt made in the early 1900s. I’ve never owned a piece of clothing that’s essentially antique, and I bought it because of its age, not despite it. I wanted to experience what it felt like to wear a piece of clothing with so much history behind it. Would it whisper or shout, and how would I respond to its call?

The skirt is made of fairly heavy, durable, textured cotton, and lined with gauze-like Indian cotton. The workmanship isn’t anything special; it’s a simple skirt and actually fairly clumsily made. As the skirt is from a time when zippers weren’t used in clothing yet, it is fastened with a couple of hooks and snap buttons on the side. The skirt has gone through several alterations: the waistband has been made first bigger, then smaller. The fabric has been mended in a couple of places and the hem has a charming dust trim.

It’s a strange feeling, almost like a badge of honor, to wear something this old. The big inverted pleat in the front of the skirt gathers in between my legs as I walk, so I’ve opted to wear the pleat slightly to the side rather than trying to find a structured petticoat to wear underneath. I have to lift the hem when I get on and off the bus or the tram in order to not trip up. On the street the fabric moves like a wave, trying to catch up to my steps. Wearing this skirt is an experience.

I am very protective of the skirt despite having owned it for such a short time, and choosing to put it on in the morning jump-starts a different type of exercise than picking a more modern piece of clothing to wear would. The thought of “styling” an antique skirt just feels wrong. It’s not about what goes with it. It becomes an act of simply wearing an antique skirt instead, which reminds me of my first ever newsletter here on Substack, where I talked about Wim Wenders’ documentary about Yohji Yamamoto, ‘Notebook on Cities and Clothes’ (1989). Wenders narrates early on in the documentary how wearing Yohji’s clothes made him feel that he was wearing “a shirt in itself and a jacket in itself, and in them, I was myself”. (It is not a coincidence that just like Lee McQueen, Yohji has also been heavily influenced by historical clothing, fabric and craft in his work, and some people feel a deep affinity to his clothes. Yohji is a romantic, dressing other romantics, and in this, there’s meaning.) Some clothes become the essence of their function when they interact with a human being, allowing the human to shine in the process of bonding. I am aware that this might all sound like gobbledygook, or at least some weird form of animism. The reasoning, though, is the same as why the gold locket my father gave me when I was four years old is meaningful to me. It’s why I like wearing my grandfather’s suspenders, or why the 120-year-old skirt has a different kind of value to me than something current. It’s not rational, but emotional.

The 120-year-old skirt is making me look at clothes and fashion differently. Current fashion is a “having a cake and eating it too” type of situation. There’s a lot of talk about self-expression through clothes within the Zeitgeist, and of finding our personal aesthetic or our style signature. We try to discover where we are located on the fashion map through analysis and careful examination. We expect it to make sense and to become ready. I’ve been on that path myself: trying to find myself in my clothes, thinking that if I just bought or owned the right clothes somehow, I would see myself clearer. I’ve photographed my outfits, counted my wears, I’ve analyzed my likes and dislikes, I’ve punched in data and calculated my shopping. I’ve learned a lot: I’ve recognized certain patterns of behavior and I’ve made better sense of my wardrobe, but I haven’t gotten any closer to seeing myself through all this. In some ways I feel that all the analysis has pushed me further outside of myself. I don’t think I’m the only one. I sometimes wonder if we’re all analyzing our personal style and our creativity to death.

The 120-year-old skirt is like the gut punch I needed. It reels me back in from the outside. It makes me feel something and I find myself responding to it, interacting with it. The skirt reminds me that our bodies are a beacon and wearing clothes is about broadcasting stories. It’s just that the stories always mature a little bit later, almost like an afterthought. It takes time for a connection to develop, for a story to find its shape, to become vocal. It’s in that space that a piece of clothing can become an heirloom, something for us to hold onto and cherish, and one day, to pass on to others.

I leave you with a video clip of Alexander McQueen’s Spring/Summer 2001 fashion show, VOSS. Enjoy!

Suomeksi:

Olen miettinyt viimeisen viikon aikana Alexander Lee McQueenia ja hänen suunnittelemiaan vaatteita. McQueenia kiinnosti historian käsitteleminen nykyajan näkökulmasta. Käsityöperinne ja vaatteiden säilyminen tuleville sukupolville olivat hänelle tärkeitä.

Historiallinen vaatetus kiinnostaa minua entistä enemmän. Työssäni pääsen lähelle aidosti vanhoja vaatteita, joissa näkyvä ja tuntuva ihmisen kädenjälki kuiskailee tarinoita entisestä. Massatuotetut nykyvaatteet eivät sen sijaan tunnu oikein miltään. Ei kai ole ihmekään, että kiintymyssuhteet vaatteisiimme jäävät syntymättä ja haalimme vaatteita kiivaampaan tahtiin kuin koskaan ennen.

Ostin 46-vuotissyntymäpäivälahjaksi itselleni hameen 1900-luvun alusta. En ole aiemmin pukeutunut näin iäkkääseen vaatteeseen. Puuvillaisessa, raskaasti valuvassa 120-vuotiaassa hameessa liikkuminen on voimakkaita tunteita herättävä kokemus, ja se muistuttaa minua siitä, että vaatteilla on oltava tarinoita, jos haluamme niiden olevan meille merkityksellisiä. Huomaan nyt, ettei tyylini analysoiminen ja puhkiselittäminen ole tehnyt minua yhtään viisaammaksi. Kiinnyn vaatteisiin, joiden kertomien tarinoiden kanssa pääsen vuorovaikutukseen — aika yksinkertaista, loppujen lopuksi. Vaatteiden tarinoiden kuunteleminen vaatii tietoa tekstiileistä ja vaatetuksen historiasta, mutta myös herkkyyttä ja kykyä astua syrjään kuluttajan roolista.

As much as I admire Allison Bernstein, the three words repel me for the reasons you mention. (I admire her because I think she is the most sustainability minded social media stylist and she shares advice in an empathetic, thoughtful and practical way.) Who cares what my three words are? I feel best and look best when I intuitively put things together without much thought and contrivance. Similarly as much as I admire Amy Smilovic’s style, “chill, modern and classic” makes me want to run away as if I dodging a cult.

The root cause, I believe, is that never have so many had so much access to garments and so much visual stimulation on social media. This has left most people rudderless, looking for a mantra on their own personal style.

Your skirt operates in another echelon. One can only imagine its origins. It might have been the only garment the original owner acquired that year. She might have thought about it for months, and intimately collaborated with her seamstress on execution. Or she might have sewn it herself, stitch by stitch. With such care and deliberation, you could not possibly come out of that with a disposable garment you were destined to become indifferent to.

Your point on "analyzing our personal style and our creativity to death" is spot on! These systems of rational style analysis have become another commodity to sell women (apps, templates, courses, services), whereas forging emotional connection to clothes is personal, slow, and impossible to package up.

I've been thinking about the different ways we engage with fashion and clothing beyond dressing for practicality. Styling seems to be about image-making, with you as the subject and clothes ancillary to an overall creative vision. Then there is appreciation of clothing as art, where you respect and embody the spirit of spectacular garments that stand on their own.

These two approaches influence how people shop, from hunting for dupes to complete an on-trend look to curating pieces with integrity and heirloom potential. Ultimately, to be a conscious consumer, both perspectives are important. Otherwise, you may find yourself shopping without care or collecting without wearability.